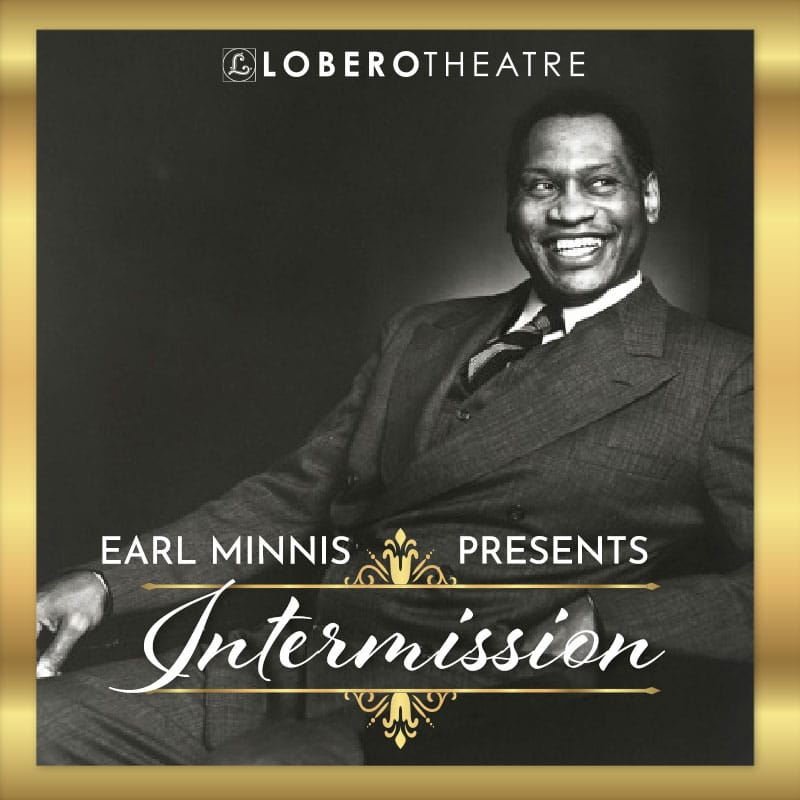

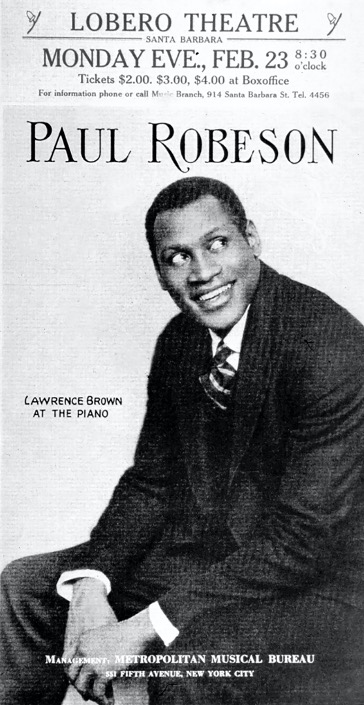

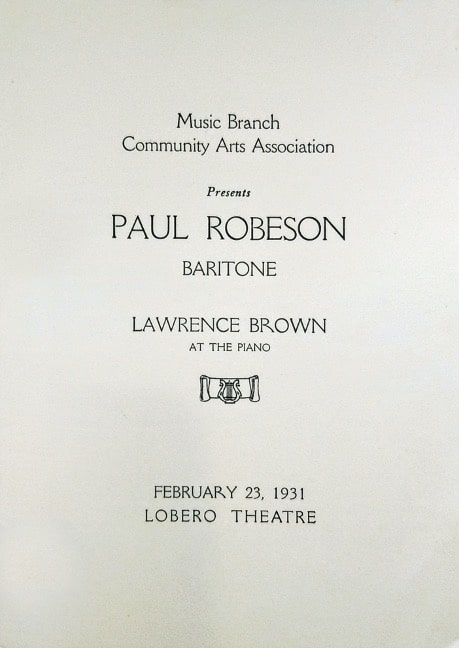

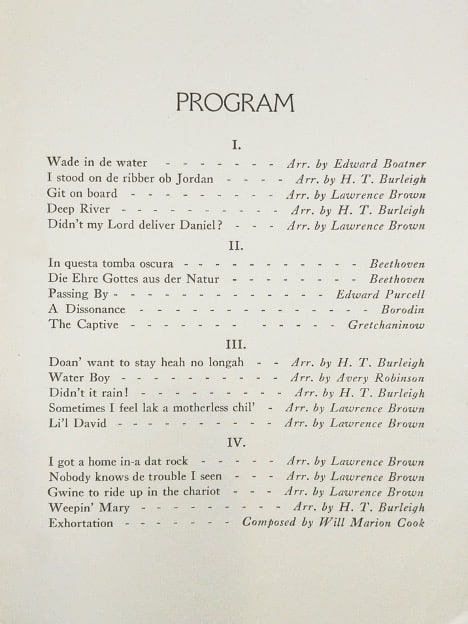

On February 23, 1931 a standing-room-only audience filled the Lobero to hear singer Paul Robeson unleash his rich timbered bass-baritone in a program that ranged from classical arias to southern spirituals.

Presented by the Community Arts Music Association (CAMA), one reviewer wrote that “the singing of Paul Robeson wrought an unaccustomed miracle at the Lobero Theatre last night and caused the sedate audience to abandon its reserve for an enthusiasm which could only find vent in shouts and bravos.”

Paul Robeson was born in 1898 In Princeton, New Jersey. His father was a Presbyterian minister who had been a North Carolina plantation slave until he escaped in 1860. Robeson’s mother was a Philadelphia schoolteacher, who died when Robeson was only 9.

In 1915 Paul Robeson won a scholarship to attend Rutgers University and became only the third African American ever to attend the private college. Robeson was an exceptional university scholar and football star and was twice selected as a first-team All-American tight end. In his 1919 valedictorian speech, Robeson asked his classmates to work for the equality of all Americans, a mission he devoted his entire life to fulfilling.

After graduating from Rutgers, Paul Robeson married, earned his law degree from Columbia University, and even played a season in the National Football League. At the urging of his wife Essie Goode, Robeson tried out for and won a leading role in the play Taboo, which debuted at a Harlem theater in 1922. Set on a plantation in Louisiana before the Civil War, Robeson’s performance received rave reviews and highlighted his acting ability and extraordinary singing voice. In 1924, Robeson landed the lead role in Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones and accompanied the play when it went on to London.

Compared with America, the Robeson’s found England to be refreshingly free from racial prejudice. Essie wrote, “that here in London they could, as respectable human beings, dine at any public place.” While theaters in New York would only allow blacks to sit in the balcony, and white hotels would refuse accommodation, the Robeson’s found London society – and Europe in general – to be much more accepting.

In 1928 Robeson played “Joe” in the London production of the American musical Show Boat. His singing of “Ol’ Man River” became a cultural sensation, and he was summoned by Buckingham Palace to perform for the royal family. The couple bought a house in London, and Robeson was cast to play Othello, one of the first black men to perform the role.

In 1931 Paul Robeson returned to America for a series of concerts. The tour began at New York’s Carnegie Hall in January and initially featured an evenly mixed program of classical arias and southern spirituals. By the time Robeson performed at the Lobero in February, the program consisted mostly of spirituals.

Robeson’s Lobero concert was a presentation of the Music branch of the Community Arts Association (CAMA) as part of its 12th season and was a phenomenal success. The Santa Barbara News-Press reported, “Long before the date of the concert, the theater was sold out. During the last few days, the demand for seats has exceeded that of any other concert the committee has sponsored. Last evening scores of persons who came to the theater optimistically hoping to gain entrance had to be turned away. Unfortunately for those who were deprived of hearing the concert, seats were not sold on the stage, otherwise another 200 persons might have listened to the magnificent voice.”

Critics raved about the quality and sincerity of Robeson’s singing. The influential theatrical producer Irving Pichel wrote,

“Robeson sang with so complete a simplicity and unaffected identification with the content of the songs that they were indescribably moving.”

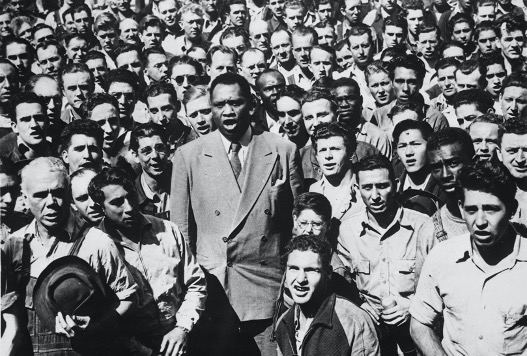

After completing his American tour, Robeson returned to Europe and increasingly became an advocate for social and political causes. As the Smithsonian Magazine explained, “After a visit to Eastern Europe in 1934, where he was nearly attacked by Nazis in Germany, Robeson experienced nothing but adulation and respect in the USSR—a nation he believed did not harbor any resentment or racial animosity toward blacks. ‘Here, I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life,’ he said. ‘I walk in full human dignity.’”

In the 1950’s, after refusing to sign an affidavit declaring he was not a Communist, Robeson was called to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Because of the negative publicity over his positive views of the USSR, Robeson was blacklisted from performing, his name was removed from the college All-America football teams, his recordings and films were removed from distribution and he was even condemned by leaders of the civil rights movement.

Yet Robeson held fast in his beliefs. “I care nothing–less than nothing–about what the lords of the land, the Big White Folks, think of me and my ideas,” Robeson later wrote, in Here I Stand. “For more than 10 years they have persecuted me in every way they could–by slander and mob violence, by denying me the right to practice my profession as an artist, by withholding my right to travel abroad. To these, the real Un-Americans, I merely say: ‘All right–I don’t like you either!’”

In 1963, suffering from chronic health issues, Paul Robeson retired from performing and public life. Essie Robeson died in 1965, and Paul passed away in Philadelphia in 1976. He was 77 years old.

Sources

- Community Arts Music Association (CAMA)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Robeson

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-paul-robeson-said-77742433/

- https://www.nytimes.com/1976/01/24/archives/paul-robeson-dead-at-77-singer-actor-and-activist-paul-robeson-the

- https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/paul-robeson-story-how-american-icon-was-driven-death-be-told-film-9874111.html

- http://archives.nypl.org/scm/20649

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eh9WayN7R-s