Interview by Stanley Naftaly on Jazz Straight Ahead KCSB-FM 91.9

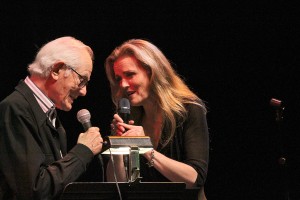

Alan Bergman and his wife Marilyn head the planet-wide list of today’s song lyricists. This phone interview was triggered because Alan, with Bill Cantos on piano and Trey Henry on bass and supported by Santa Barbara’s favorite jazz chanteuse, Tierney Sutton, was scheduled to perform at the Lobero Theatre Saturday evening, May 17, 2014 at 7:30.

Stanley Naftaly

Jazz Straight Ahead, KCSB-FM

JoyousNoise Productions

S Alan, thank you for being with us.

A Thank you for having me.

S So, your long career together has made you and Marilyn one of music’s premiere lyricist teams. And I understand that, at 12 years old, you already knew you wanted to be a song writer.

A Yeah, it was more than wanting, I had to be a song writer.

S You had to be a song writer. I’m interested in how that came about and in particular, how your family life prepared you for that early decision.

A Well musically, if you were Jewish and you lived in Brooklyn, when you were a child, when you were six years old you got piano lessons. That was automatic.

So, I got piano lessons and I loved that and I’d sit by the radio in those days and listen to the bands. It was the early start of the Swing Band Era; Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey and Glen Miller and so forth. And it’s interesting because their songs – what they played, the pitch was wonderful. They were really great songs. And those were the songs that molded the opinions of listeners all over the country. It was the time of the musical environment in this country when the people who were picking the songs were musicians, they weren’t A&R men, they weren’t executives of record companies, they were musicians and they had great taste. You heard Jerome Kern, Cole Porter and those wonderful people, composers and lyricists in those days. You heard them because of these new good songs. And I heard them as a kid and I said, “God, that’s wonderful. I have to do that.” It was the generation that was influenced and listened and took it in like osmosis. S So all of this was present in your home as a child?

A Yes, yes.

S And your parents were in favor of your idea?

A Yes, my father and mother were very supportive except they said “Hey, you’ve gotta make a living.” Well it was hard.

S And clearly, you succeeded.

A The dream came true.

S Absolutely. What a wonderful story. Now I understand how your family life prepared you for that.

A There was a lot of classical music and concerts because I studied classical piano. When I was 8, 9, 10, in those years there was a Conductor of the New York Philharmonic, a man by the name of Walter Damrosch who preceded Leonard Bernstein in billing children’s concerts. My mother took me every Saturday to the concerts at Carnegie Hall and I got a great musical education that way. And oddly enough, Marilyn’s mother did the same thing with her and we could have been in Carnegie Hall together.

S Apparently it was your destiny to end up together.

A We were born in the same hospital. And Barbra Streisand was born in the same hospital, so it must have been something in the water.

S You were fortunate enough to be mentored by Johnny Mercer.

A Oh absolutely.

S I can’t imagine a more profoundly meaningful relationship for you.

A Oh it was just wonderful, always very encouraging. You know he started Capitol Records. There was a man by the name of Glen Wallach and man by the name of Buddy DaSilva who was part of the team DaSilva, Brown and Henderson. They were wonderful song writers. Buddy DaSilva became the head of Paramount Pictures. He had a bigger career than just writing songs. He wrote “Button Up Your Overcoat” and a lot of songs in those days. One day in 1955, I was writing both music and lyrics in those days, Johnny came to me and we were in one of our sessions and he said he was gonna produce an album (it was an album in those days) with Bing Crosby and Louis Armstrong. And he said to me “go home and write a duet for them.” And I did and he came back and he said “let me hear it” and I played it for him and he said “that’s perfect, we’ll do it.”

S And what was it?

A It was a song called “Let’s Sing Like a Dixieland Band.” And Bing Crosby and Louis Armstrong did it with Billy May. It’s available I think in CD form now. And oddly enough, on the date Mr. Crosby came over to me and said “Al I love your song, but you have indicated that I should scat sing and Louis Armstrong should scat sing.” I said, “Yes, there’s a chorus for each of you.” And he said “Could you please rewrite it so I don’t have to scat because he’s so great I can’t scat on the same record with him.” And Johnny Mercer said to me “Welcome to show biz, kid. Go over there and fix it.” So I did. I went over and fixed it on the date, and I was sweating a lot. But there you are. And they made a wonderful record.

You know, Johnny Mercer was one of the most versatile of all of the lyric writers. He could write anything. He could write I love you. He could write a lot about birds, besides “Skylark” there’s a lot of other bird songs. He could write very funny material. People don’t know this about him, but Benny Goodman had a radio show in the late ‘30s and Johnny Mercer was the MC of it. And they gave him 3 to 4 to 5 minutes every broadcast where he would take the news of the day and make a blues song out of the news of the day extemporaneously. And he’d play it and sing it, yeah. He was a great singer. And he would create that, whatever was in the news; he would create a song about it. Not just one item, but many items in the blues genre and it was fantastic. Of course he’s got many, many records out and great, I mean a wonderful singer. People don’t know, people think he’s just a lyric writer but he wrote music and the lyrics to a lot of songs like “Dream”, “Something’s Gotta Give.” He wrote the music to that too. He was fantastic.

S Talking about Johnny Mercer, years later you received the first Johnny Mercer Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award.

A Yeah Marilyn and I did, that was absolutely thrilling.

S Talk about what goes around comes around, what a lovely story.

A And oddly enough, the first piece of sheet music I ever bought when I was 11 or 12 was a song that Johnny Mercer was one of the writers of, a song called “Lost” which a lot people probably don’t know. “Lost, the moment I met you. Lost or strayed or stolen away, finders keepers, losers weepers.” I still remember that song.

S About you and Marilyn, in all the research I did it’s been difficult for me to draw any sort of a line between you two. Are you as much of a unit professionally as it seems?

A Oh absolutely. We’ve been writing together since 1956 which is when we met in that year. We met and we wrote a song on that day, it wasn’t a very good song but we loved the process and we’ve been writing together ever since. And about a year so later, we married and we’ve been married 56 years.

S Wow 56 years, that’s marvelous. That was the assumption I made. It always felt like….I don’t know if you remember but we met in the Green Room of the Lobero not too long ago when Tierney was there.

A When Tierney was there? You know Tierney is gonna sing a couple of songs with me.

S I do. That was one of the things I wanted to bring out. She is Santa Barbara’s favorite – I don’t know if Chanteuse is appropriate.

A That’s a good word. She’s a wonderful singer and human being too.

S I know, I’ve had the opportunity to get to know her over the years. She’s marvelous and she has one of the most purely beautiful voices I’ve ever heard.

A Absolutely

S So she’s going to be there on Saturday night. Will you be singing your own songs?

A All songs that Marilyn and I wrote with wonderful and great composers like Michele Legrand, John Williams, Dave Grusin and Henry Mancini.

S It will be a treat, there’s no question. Is there any difference at all in what you and Marilyn do in the partnership?

A No – what it is, is that one is the creator and one is the editor and those roles change within seconds. It’s like pitching and catching. The only thing in the collaboration that Marilyn doesn’t do is sing. After we write 8 bars or so, I sing them because lyrics are meant to be sung. Unlike poetry where you can read poetry at any cadence that you want to, lyrics have to sit on those notes as if they were inevitable. And the use of a word or not to use a word is whether it sings on those particular notes that you want them there for. That’s what lyrics have to do. That’s our exploration. We write 90% of the time to the melodies and so we have the melody to work with, to inspire us. The rhymes are in the melody and we play them over and over again until we get an idea that we like and when we’re writing in a dramatic context, then we have the theme, the characters. If it’s a movie, we have the scene to look at and that’s the way it works.

S Just out of curiosity, why does she not sing, she doesn’t want to sing?

A No, no, of of course she can sing. I’m just talking about in the process I sing.

S Ok, the next question is about your singing. It seems that recently you have expanded your activities to include singing.

A A few years ago a gentleman who owned a record company in Germany – we did a concert in New York and he came up to me after the concert and said he loved the way I sang and would I make a record and I said “I don’t know about that.” And he kept after me for a few years and I said “Ok, you seem to be serious about this.” So he flew Marilyn and me to Berlin and he organized an orchestra and a wonderful orchestrator and we made this CD that when Universal heard it they loved it and Verve released it and the reception has been just terrific, especially from jazz instrumentalists and jazz singers all over the country. They email me about how much they think of it.

S Are you speaking of “lyrically?”

A Yeah, that’s it

S Excellent. I’ve played “Nice and Easy” and “What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life” today. What would you like me to play at the end of the interview?

A Well there’s a favorite song of ours that Marilyn and I wrote for each other called “Love Like Ours” that we like a lot.

S Ok I see it.

A There are wonderful people on there. Frank Chastenay is the pianist, he lives in Germany, wonderful pianist and Eric Bruner, the trumpet player on “Nice and Easy” is a wonderful soloist, and Chris McBride, the bass player and Jeff Hamilton, the drummer –The producer flew them over because he didn’t like the rhythm sections in Germany.

S Well you can’t do any better than those two. I was first amazed by Jeff Hamilton shortly after Shelley Mann’s death,.

A Marilyn and I wrote in 1956, shortly after we met, we wrote a nightclub act for Buddy Rich, so we know about drummers. Oh Buddy was some drummer, oh my God.

S I know this isn’t really my point, but my favorite Buddy Rich story is when he fired his band.

A Oh yeah and Berkley School of Music sent him a whole new band.

S No I didn’t know that.

A The funniest story about Buddy is he was going in for an operation, you know the brain operation and on the way to the surgery, the anesthetist asked him “are you allergic to anything?” He said “Yes” and the doctor said “What is that?” And he said, “country music.” That’s a true story.

S I noticed going through stuff to prepare for this that “You Must Believe in Spring” is among yours and Marilyn’s songs. I’ve always associated that piece with Bill Evans.

A The melody is by Michele Legrand and Bill played it. There are two albums out I think with that title from Bill. Then he made one with Tony Bennett singing. That’s a wonderful melody.

S I’m curious, do you and/or Marilyn ever compose the music?

A Well I used to, but sometimes we do suggest musically a way to fix something or make it hopefully better or all right. But we write – neither one of us has that kind of ego, it’s the song that matters and we write with such great composers, some of whom I mentioned before and others like Johnny Mandell. You know it’s the song that has to be great or as great as you can make it. And they write terrific, Dave Grusin and Michele and John Williams.

S Johnny Mandell is actually going to bring his 17 piece band to Santa Barbara in a couple of weeks.

A When is that?

S I’d have to look it up. Ian Bernard, who is………

A I thought he did it already, but I guess not.

S No, no I think it’s late in May. I hope so because I’m planning to do an interview with him.

A He’s terrific, I mean Mandell is one of the great orchestrators, but he’s also a wonderful song writer. We’ve written a lot of songs with Johnny; “The Shadow of Your Smile,” “Emily,” “Where Do You Start?” “Cinnamon and Clover,” a lot of songs, a wonderful song writer. He sent us one the other day.

S Ok let’s change the subject a little bit. My own advancing age has shown me that the rewards I get from my work in music have evolved somewhat from personal to, you might say, more emotional or spiritual, as maturity enters the picture. The question is, do you notice this phenomenon in your life and work? It’s hard to describe but maybe it’s less self-related and more of a feeling of fulfillment at just continuing the work and adding to the art form. Does that make any sense to you?

A Yeah, well we love to write and I’ve said this before but we love to write and when you do something you love to do with somebody you love, why ever do you want to stop?

S That’s true.

A And there’s something spiritual there, you know, it’s there. I mean, we wake up in the morning, I play tennis every day, I come home, I make breakfast for Marilyn and then we go to work and we’re a few feet from each other, looking at each other, writing and singing and there you are. And we have a wonderful daughter and a granddaughter and we’re healthy….

S Sounds good to me.

A Yeah, how better can it be?

S No, I can’t imagine how it could be any better than that.

A And we go, we try every Friday to go to our little house in Montecito and it’s so nice and quiet. Very few people have the phone number so we can work uninterrupted and life is great.

S I’m really enjoying this conversation, Alan, thank you.

A Oh me too.

S Good. Do you have any specific plans for future projects?

A Oh yes, 3 or 4 things. A Broadway show that we did is being revived in London and we’re going to have to write a couple of new things for that. Marilyn and I optioned a book that will be made into an animated movie that we are writing the score for with Dave Grusin. It’s called “Broadway Chicken” and it’s about a chicken that becomes a Broadway star. It’s a wonderful book that we’ve been after for a long time and we finally have optioned it. We have an idea that when we finish writing will hopefully premier at the Geffin Playhouse. We wrote a show with Sy Coleman just before he died — a great composer. It’s about jazz, about the people who sing it, who play it, people who come to hear it, it’s all about that environment and we’re hoping that it will be put on in New York. It played here at the Mark Taper Theater for a limited engagement for 10 weeks and it was sold out every night so hopefully, it will go on. That’s what we’re busy with at the moment.

S At the beginning of this I said that I saw you as the leader of today’s version of Tin Pan Alley. What do you think about that? Do we have a version of that?

A I wouldn’t say that. My definition of Tin Pan Alley would be of the people who wrote songs, but they weren’t in dramatic context at all. They were songs not from a show or a movie, in those days there was no television. We were never interested in writing songs for records. We had to do that in order to get to where we wanted to write in dramatic context. The fact that in 1958 there was a cultural craze in this country and we wrote a song called “Yellowbird” that became a big hit. That paid the groceries for a little while. And then in 1960 we wrote “Nice and Easy” for Frank Sinatra and that gave us a little reputation and got us a movie. Then there was a dry period and in 1966 there was a knock on the door and it was Quincy Jones who said “I’m writing a picture called “In the Heat of the Night” and Ray Charles is going to sing the song, would you write it with me?” And that was for a director by the name of Norman Jewison and he directed “In the Heat of the Night” and the next film that he did was “The Thomas Crown Affair” and he asked us to write a couple of songs for that, then Michele Legrand and we wrote “The Windmills of Your Mind” and that won the Academy Award and that kind of made it easier for us to get a job in the context that we wanted to write for. So it’s different than Tin Pan Alley.

S Right, and you just educated me considerably for which I thank you. If I understood what you said, Tin Pan Alley was writing songs without a context, without a dramatic context.

A Most of the time, absolutely. Then in the ‘60s, we were not part of the Brill building which fostered Neal Diamond, Bacharach and David and so on,

S Well help me out here a little further: I have always considered people like Cole Porter to be part of Tin Pan Alley. Is that incorrect?

A Oh no I wouldn’t say that. Cole Porter was a theater, Broadway writer, like Rodgers and Hammerstein, like Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin. If you talk about history for instance, you might be interested to know that there were two songs that were written in 1910 that changed American music, American popular music. Those two songs, one was written by Jerome Kern called “They Didn’t Believe Me.” The other song was written by Irving Berlin was “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.” Now those two songs were not written in the tradition of European operetta music, which was the popular music in those days. Victor Herbert, Sigmund Romberg, those people. It was their music that was popular and in the theater, “Naughty Marietta” and operettas like that, then these two songs came which changed the environment entirely. Popular music was changed by those two songs.

S Ok, I’m not exactly clear on how popular music changed from those two songs.

A Well it wasn’t the songs now from operettas and it wasn’t European-based kind of songs. They were strictly American those two. That’s how it changed.

S I get it. Well you said 1910 that would be when jazz was still a new art form.

A Oh yeah, and the jazz players, who had great taste, would take these songs from Broadway shows and make standards out of them. Because the melodies were wonderful, the chord changes were wonderful and they loved those songs. They were great songs, the Gershwins; they changed the face of it.

S Ok, I’m beginning to understand. Are we running out of time?

A No, we’re fine, we rehearsed all morning. Tierney was here.

S Ok, you and Marilyn have been awarded virtually every accolade available. Is there any accomplishment or anything still missing at this point?

A Well we’ve written two shows for Broadway. We haven’t written one that was successful; we’d like to do that. As I said we are writing an animated feature which we always wanted to do. We had a wonderful time writing “Yentl.” That was a great experience. You know, it’s not heavy lifting; you just pick up a pencil and write.

S That’s hilarious. All those accolades don’t mean anything we just picked up a pencil.

A Well you know what the accolades do? Here’s what’s good, for instance: winning the Academy Award, or even being nominated for an Academy Award. It gives the song a platform, where people will recognize it. They’ll hear it a little more often than one that wasn’t nominated. When it’s initiated, when it’s just starting out, that platform is very important and it’s always nice to be awarded, especially from your peers, it’s terrific.

S Yeah, as you say, especially from your peers. That I can understand.

A Oh absolutely

S Is there anything further you would like to share with us? Things I haven’t thought to ask you about?

A Well I hope a lot of people come Saturday night…. It’s a big theater.

S Let me go back and remind folks that the reason we’re talking with Alan Bergman is that he and Tierney Sutton will be on stage at the Lobero Theater……..

A And a wonderful pianist, Bill Cantos and bass player, Trey Henry. They’re terrific musicians.

S And Henry is one of the members of Tierney’s band.

A And he’s played for me for a long time and Bill Cantos plays piano for Herb Alpert and has been for years.

S So that’s going to happen Saturday night at the Lobero at 7:30, not the usual 8:00 start time, but the 7:30 start time and you can get tickets at the box office at the Lobero at 33 East Canon Perdido, you can do it by phone at 805-963-0761 or you can do it on line at Lobero.com where you print out your tickets at home. So hopefully we will jam the place and we’ll all have a good time. I know I’m going to.

A Ok you come back and see us.

S I definitely will, I wouldn’t pass it up. Thank you, you have been kind and amazingly generous – really, it’s been a privilege and a pleasure talking with you Alan.

A And mine too.

S Well thank you for saying that. Take care.

A You too, stay well. Bye

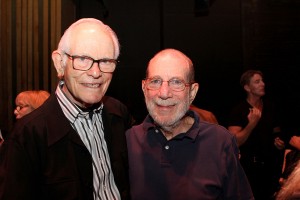

*Photos by Monie Photography